Changes: The Many Faces Of David Bowie

[Originally published on TIDAL Read]

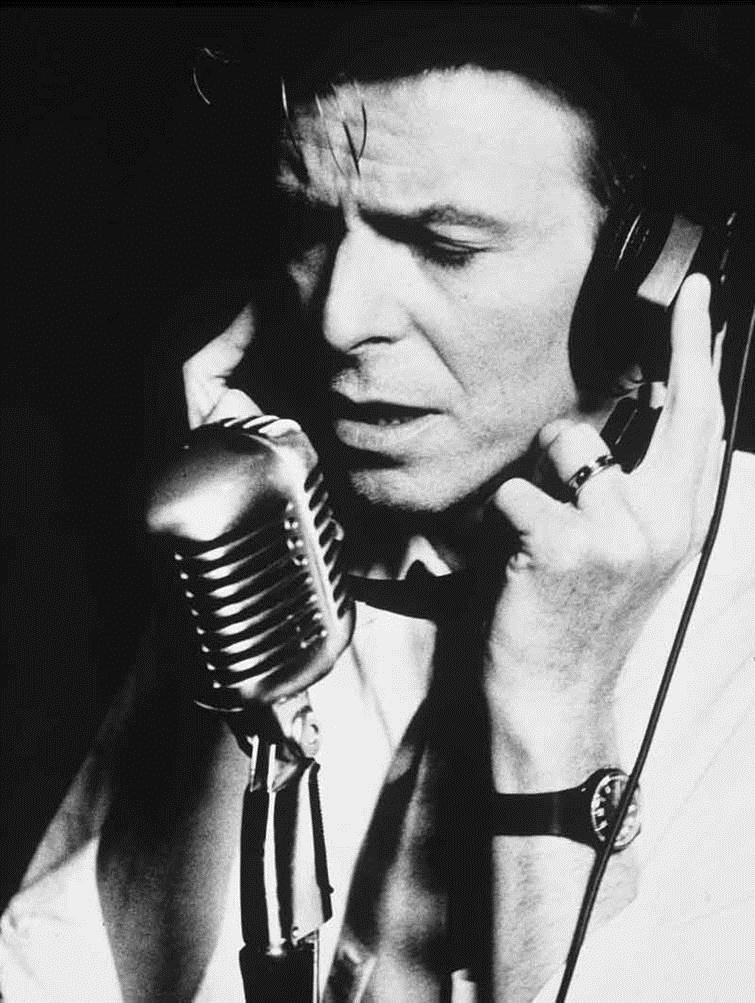

David Bowie was the ultimate chameleon.

In his 50+ year music career — not even mentioning his many other courtings in art, film and fashion — the British icon continually shape-shifted to become one of the most pioneering and influential artists of his time.

He’s had various peaks in creativity and popularity, but he never stopped his perpetual evolution — from pop singer to alien from Mars, slim cabaret man, art rocker, new wave chartbuster, electro enthusiast and far beyond — incessantly innovating his sound with the same rapid pace that he reinvented his outer appearance and stage persona. Just last Friday, on his 69th birthday, Bowie released his stunning 25th studio album, Blackstar (styled ‘★’), marking an exciting new venture into jazz impressionism.

This Monday morning we woke up to the mournful news that Bowie had passed away, following a private 18-month battle with cancer. According to a statement on his Facebook page, he died peacefully at home, surrounded by family.

To commemorate the conclusion of this incomparable artist’s brilliant life and career, we’ve attempted to break down the many faces of David Bowie into 11 distinct phases. While no clean lines could contain his amorphous genius, we hope it serves as an introduction to his remarkable legacy.

* * *

Davie Jones

Playing on his birth name, David Robert Jones, Bowie’s original stage moniker was Davie Jones, which he later changed due to confusion with The Monkees singer Davy Jones. Declaring his intention to become a pop star from the age of 15, Bowie hopped between a heaping handful of bands, repeatedly moving on for his dissatisfaction with his collaborators.

The Davie Jones phase is Bowie emulating the Sixties pop singer of the day, before he found his own voice. Playing with entertaining albeit unrealized stylings of baroque pop, psychedelia and music hall (vaudeville), his 1967 self-titled debut, David Bowie, failed to chart and is thought of as something of a throwaway in comparison to the greatness soon to come.

Space Oddity

Released shortly before the Apollo 11 moon landing, his breakout single, “Space Oddity,” became a U.K. hit in part because of its good timing, but it also signaled the arrival of an original voice. Fed by his drama studies in London, Bowie became intent on molding a distinct stage persona. Adopting an androgynous appearance, and frequently donning a dress on stage and in the press, the albums Space Oddity (1969, originally self-titled like his debut), The Man Who Sold the World (1970), and Hunky Dory (1971) encompass David Bowie’s first fully-realized phase.

Musically, Bowie embraces largely acoustic, folk rock stylings — though The Man Who Sold the World is notably more hard rocking, which some have called the origin of glam rock — with existential lyrics about peace, love and morality, as well as songs paying homage to the idols (Bob Dylan, Velvet Underground, Andy Warhol) he would soon stand in good company with. Containing classics like “Changes,” “Oh! You Pretty Things,” “Life on Mars?” and “Queen Bitch,” Hunky Dory is the standout album of the period – and would have defined a fine formula for continued success if David Bowie had had any interest in standing still. He didn’t.

Ziggy Stardust

Aware of the attention his initial success granted him, Bowie swiftly reinvented his image into something ever more radical. Consciously combining the persona of Iggy Pop and the music of Lou Reed, he invented the fictional character Ziggy Stardust, a bisexual alien rockstar, and renamed his electrified backing band The Spiders from Mars.

A loose concept album, the epically titled The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars (1972) is set up as Ziggy comes to earth with lessons for humanity in the final five years of his life, and covers themes of sexuality, drug use and the artificiality of rock ‘n’ roll. Combined with his fluid sexuality and outrageous outfits, Bowie fully abandons folk aesthetics to coin the defining brand of glam rock.

Inspired by his subsequent U.S. tour, Bowie’s follow-up, Aladdin Sane (1973), is commonly summed up as “Ziggy goes to America,” as is evident in songs like “The Jean Genie” and “Drive-In Saturday.”

Young American

David Bowie moved to the U.S. in 1974, and his new surroundings had an obvious effect. Namely, he adopted a new sound heavily steeped in American funk and soul.

A post-apocalyptic concept album themed around George Orwell’s seminal novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1974′s Diamond Dogs holds remnants of Ziggy Stardust and glam rock — particularly on hit single “Rebel Rebel” — but with the omission of the Spiders from Mars as his backing band, Bowie’ is clearly moving on.

Young Americans (1975) is the full arrival of a new David Bowie. Deeply infatuated with the R&B and soul music of the day, he strove for a truly authentic soul sound, bringing in a young Luther Vandross and members of Sly & the Family Stone to the recording studio. Bowie himself called the sound “plastic soul,” describing the album as ”the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey.”

The album was recorded in the soul capital of Philadelphia, with the exception of “Fame” and a reimagined version of The Beatles’ “Across The Universe,” produced inside Abbey Road Studios with none other than John Lennon.

The Thin White Duke

The Thin White Duke was David Bowie’s last “character” in the formal sense — not to mention his most infamous. Based on the role he portrayed in the film The Man Who Fell to Earth, using a still from the film for its album cover, he is most associated with the acclaimed Station to Station (1976).

Viscously fueled by Bowie’s paralyzing cocaine habit at the time, The Duke is a monster in disguise: ostensively civilized, crooning of love and impeccably dressed in cabaret-style garb, but in fact a hollow, bitter and certifiably mad on the inside.

The album itself is one of the most influential and critically-hailed, as well as his most cryptic and dense. The songs are darkly-themed and obsessed with the occult, but cunningly masqueraded as romantic ballads. Though still washed with the soul and funk of Young Americans, the album transitions into his next phase with Krautrock-inspired synthesizers and motorik rhythms, the blend of which might be most easily heard on “Golden Years.”

Ich bin ein Berliner

Spurred by an interest in the music exports of Germany — especially the blossoming krautrock scene led by bands like Neu!, Can, Faust and Kraftwerk — David Bowie escaped to West Berlin in 1976 where he began the recording of his eleventh LP, Low. The album commenced what is now known as “The Berlin Trilogy,” as well as Bowie’s collaboration with Brian Eno, who helped contribute to the album’s overall experimental, looming and electronic soundscapes.

The two continued their work together on Heroes, an album that further developed the minimalism of Low, while incorporating pop and rock elements. Robert Fripp, guitarist in the prog rock band King Crimson, was called in by Eno, and his playing provided the songs with an essential undercurrent of frenetic, muscular energy. This is best exemplified in the outstanding title track – building on the droney ambience that Eno developed on his own solo debut, Here Come the Warm Jets (1974).

Now completely liberated of his drug addiction, Bowie went on to record Lodger (1979), but because Bowie is Bowie, the album once again seeks new pastures, incorporating new wave and world music into the mix. Unlike its predecessors, this Lodger doesn’t include any instrumentals, and is generally more accessible and pop-oriented, but still considered the weakest piece of the trilogy — unjustly so, some might argue.

New Wave

David Bowie introduced us to the ’80s without ever losing his avant-garde edge, bringing various aspects of his multifaceted history into a new, more personal phase. Still ahead of his time, he was also looking backwards and peeling some off his masks.

“On Scary Monsters, he comes out fighting. Fusing the sheet-metal textures of the Eno trilogy into something darker and more dense,” Rolling Stone wrote in their 1980 review, noting how he met the new decade with nervous voyeurism and no hope for redemption. Bleak, harsh, paranoid, loud and in many ways uncompromising, yet still easily accessible and familiar, Scary Monsters is an album about alienation and what happens when estrangement becomes not only an illustrative concept but a code to live by, and it’s frequently hailed as one of Bowie’s true masterpieces.

Bowie also returned on top of the charts with “Ashes to Ashes,” followed by his collaboration with Queen on “Under Pressure” in 1981, foreshadowing the commercially appealing and pop-friendly Let’s Dance in 1983. Working with Nile Rodgers of Chic, Bowie created a row of smash hits (“China Girl,” “Modern Love,” “Let’s Dance”), presenting us a more upbeat, funky and shiny version of David Bowie.

This was David Bowie mastering being a pure pop icon – looking younger and healthier than in years, creating a soundtrack for the masses along the way. Those disappointed with him not bringing on yet another mask, might have missed just that.

Tin Machine

After nearly two decades as a solo artist, most of them as a superstar, David Bowie may have just felt like a break from the spotlight. Following the popular smash of Let’s Dance he released a couple of uneven, and largely uninspiring, albums with Tonight (1984) and Never Let Me Down (1987). The latter was followed by the gigantic, exhausting and poorly received Glass Spider World Tour.

In an artistic dead end, he hooked up with old partner Reeves Gabrels, who is largely responsible for helping Bowie stake out a new course. Calling in brothers Tony and Hunt Sales, Tin Machine was born as a band of equals, with no particular leader. Finding inspiration from bands like Pixies, Cream, Glenn Branca and Jimi Hendrix, Tin Machine aimed for a harder, jam-based sound, described by AllMusic as “hard-edged guitar rock with an intelligence missing from much of the work of that genre at the time.”

Their debut, Tin Machine I, was followed by a low-key club tour in stark contrast to the Glass Spider extravaganza, allowing Bowie a more anonymous and playful role as a band member. Critical reviews were mixed and some fans were confused, but Tin Machine was favorably received by many, and is now seen as a precursor to the coming grunge explosion.

After a short hiatus, Tin Machine resurfaced with Tin Machine II in 1991. Their last effort was not considered such a success, and the band split up after a lengthy tour, marking a new era for a refreshed David Bowie.

Electronic

After marrying his longtime wife Iman in 1992, David Bowie moved back to America and recorded his first solo album since Tin Machine. Reuniting with Nile Rodgers and making newfound use of electronic instruments, the soul-, jazz- and hip-hop-influenced Black Tie, White Noise (1993) birthed three popular hits, notably “Jump They Say.” Released the same year, the critically-acclaimed TV soundtrack album, The Buddha of Suburbia, mixed electronics with the alternative rock of the day.

In another reunion, Bowie teamed up with Brian Eno for 1995′s Outside, an industrial-influenced concept album planned as the first volume in a non-linear story about art and murder featuring characters based on a short story written by Bowie. Reactions were mixed when David Bowie chose Nine Inch Nails as his partner for the subsequent Outside tour, but the experience led to Trent Reznor’s participation on 1997′s edgy Earthling, which played with British jungle and drum ‘n’ bass sounds and saw Reznor re-recording and remixing single “I’m Afraid of Americans.”

Both Outside and Earthling were critical and commercial hits, suggesting that by the turn of the new millennium, David Bowie had reached untouchable status.

The Aristocrat

At the end of the Nineties Bowie moved away from the heavy electronic elements that had influenced his last few records in order to perceive a more straightforward, relaxed and – at times – almost aristocratic sound. On 1999′s ‘hours’… he makes use of live instruments and creates an overall sense of melancholy and millennial angst, at times even cranking up the guitar to deliver electrified rock ’n’ roll cuts like “If I’m Dreaming My Life” and “The Pretty Things Are Going To Hell.” Other highlights include the beautiful lament “Seven” and the opening track “Thursday’s Child.”

The general sense of plaintiveness only grew more intense on the follow up Heathen, from 2002. The album is generally considered somewhat of a comeback for Bowie in the U.S., containing such gems as “Slip Away” and “Slow Burn”. It also marked the return of producer Tony Visconti who provided for the album’s eerie and epic sound.

Only a year later, Bowie and Visconti teamed up once again to create Reality – Bowie’s 23rd studio album. But instead of dwelling in melancholy, Reality is a mature, riveting and – well – fun rock album channeling classic Bowie circa-Scary Monsters.

The Comeback

Following a decade-long hiatus, with fans and critics alike assuming he had retired for good, David Bowie released The Next Day in March 2013. Hailed by the New York Times as “Bowie’s twilight masterpiece,” with cover art playing on the classic cover of Heroes, the record was universally acclaimed for it’s expressiveness, originality and intelligence, proving as much or more than ever, David Bowie is making records only David Bowie could make.

Which brings us to Bowie’s swan song: Blackstar. Reportedly inspired from recent sources that include Kendrick Lamar, Death Grips and Boards of Canada, the album was produced with by his by-then inseparable intimate Tony Visconti and recorded with a cutting edge combo of New York jazz musicians (plus LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy playing percussion on two tracks). Calling it one of the most “aggressively experimental records” Bowie has ever made since the ’70s, Rolling Stone’s David Fricke called Blackstar “a ricochet of textural eccentricity and pictorial-shrapnel writing.”

It is with heavy, sullen hearts that we wave goodbye to David Bowie – the man who fell to Earth and continuously changed the world in the image of his ever-evolving art. There will never be another like him.

[Images courtesy of Sony]

[Words by Bjørn Hammershaug, Jonas Kleinschmidt & Ryan Pinkard]